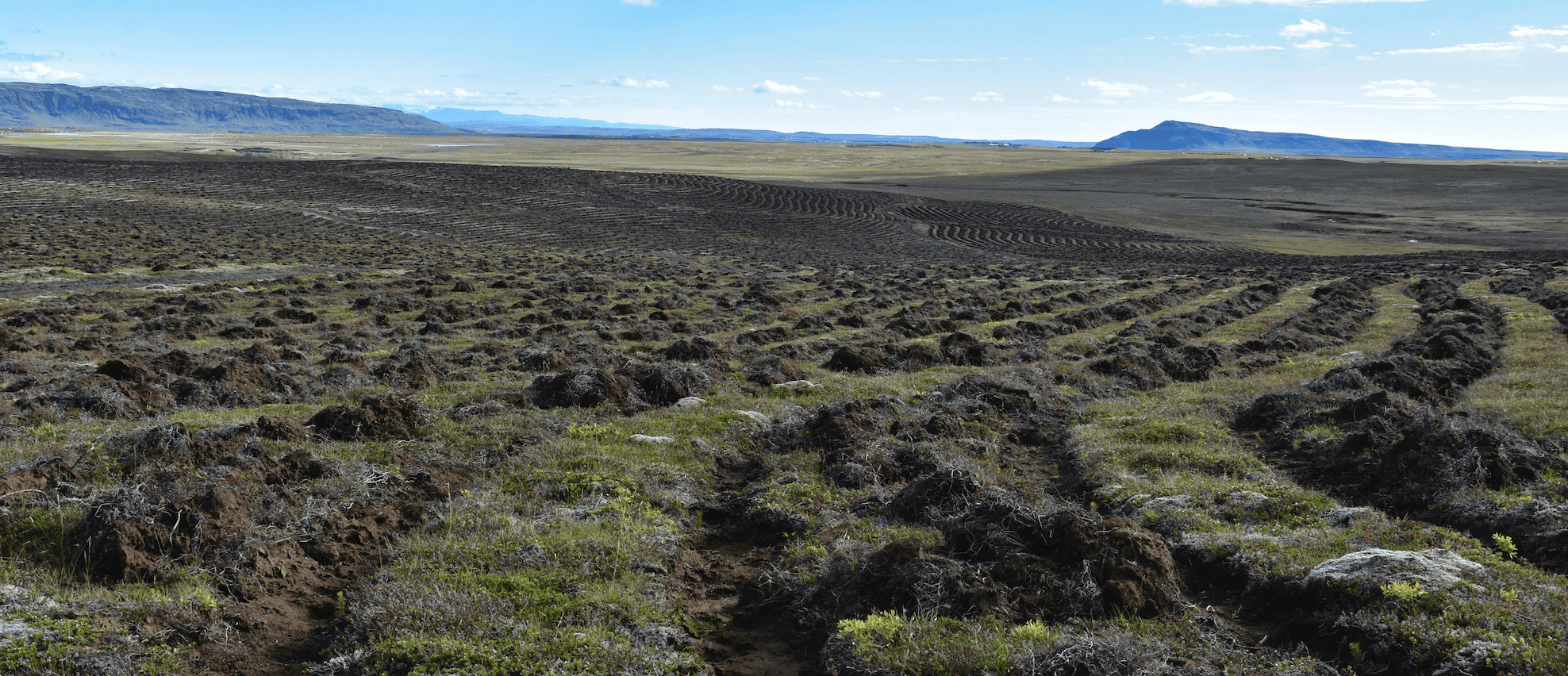

Mynd: Sigurður H. Magnússon

12 December 2023 | Sigfús Bjarnason, Andrés Arnalds and Sveinn Runólfsson

Forestry in Iceland’s Fragile Nature

This article was initially published in The Geographer (December 2023).

Over a millennium ago, when humans first settled in Iceland, it is estimated that birch forest and shrublands covered 20-40% of the land. The Book of Icelanders paints a picture of a landscape covered with wood from the mountains to the sea. The settlers burned woodlands to establish grazing areas and to make charcoal for fuel. Over the centuries vulnerable soils, sheep grazing, volcanic activities and colder climate resulted in a more or less treeless land, vegetation atrophy and eroded soils.

In Iceland, apart from the juniper shrub, there are no native coniferous species. Native tree and shrub species are birch, willow and rowan. Forestry involving non-native species has been conducted since the dawn of last century, initially on a relatively modest scale. A majority of Icelanders are in favour of forestry and there are local forestry associations in most Icelandic communities.

Forestry in Iceland is currently undergoing a profound transformation in terms of scale, methods, and objectives. The international voluntary carbon market is showing growing interest in harnessing Iceland’s potential for carbon capture projects. As a result, new stakeholders are entering the arena, and the state Forest Service anticipates a sevenfold increase in the annual allocation of land areas for forestry in the near future.

Friends of Icelandic Nature

The 2019 Forestry Act required preparation of a 10-year forestry strategy. The appointed ministerial committee did not reach consensus. The majority favoured a vast increase of coniferous tree planting, using Sitka spruce, Lodgepole pine and larch species, as well as the non-native Black cottonwood.

This was opposed by many individuals from the academic, scientific and environmental and cultural heritage communities who eventually founded an NGO called Friends of Icelandic Nature. The main objective of the NGO is to promote a better ecosystems approach to forestry in Iceland and to apply a precautionary principle when it comes to use of non-native species.

In August 2022, a new combined strategy for forestry and soil conservation was published including as a guiding principle to promote the protection, development and integrity of ecosystems based on an ecosystems approach.

A large part of Icelandic nature has little or no protection from the impacts of forestry. The Friends of Icelandic Nature regard the current forestry plans for carbon capturing as being a serious threat to biological diversity and bird life, cultural and geological heritage and the unique open Icelandic landscape.

We focus on raising awareness of the risk of using non-native species because of the significant impact they will have on the Icelandic nature and landscape in the coming decades when planted at the foreseen scale. Generally, our members acknowledge that forestry comes with various advantages, but it also comes with a significant downside. Forestry has to be planned with great care, considering the long term effects, and honouring precautionary principles. Wide consultation is essential to live up to the emphasis of the government strategy on an ecosystem approach. Our motto is Right tree in the right place.

Whimbrel. Iceland has an international responsibility for many bird species where more than 20% of the European populations either breed in Iceland or stop there during migration. Six responsibility species will be severely affected by land changes associated with extensive forestry.

Photo: Tómas Gunnar Grétarsson

Carbon forestry

Over recent years several actors in Iceland have offered tree planting to companies and individuals (including tourists) to compensate for their carbon footprint. There is an increasing awareness in Iceland that buying these carbon offsets can be regarded as ‘green washing’ – a view that was recently supported by the Forest Service. The projects are not certified and the calculation of a neutral carbon footprint is based on offsetting a time limited carbon footprint with the amount that the trees will possibly capture during their 50-60 years lifespan.

The Forest Service launched a set of requirements for carbon capture projects in 2022, making Icelandic forestry projects more attractive to the voluntary carbon market. The first project was certified against these requirements at the end of 2022. The standard addresses the green-washing nature of earlier uncertified projects: the carbon units cannot be used to offset carbon release until after measurements show that the carbon has really been captured. The initiative is drastically changing the scale of funding from the voluntary carbon market.

The Friends of Icelandic nature are opposed to many current and planned carbon capturing projects and claim that the Forest Service requirements do not provide sufficient guarantees for wide consultation, assessment of environmental risks and protection of biodiversity. The NGO also claims that the estimate of the amount of captured carbon does not take into account possible changes in soil carbon. We also find the additionality of the carbon capturing projects to be questionable when compared to the carbon capturing potential of a restored natural ecosystems. Furthermore, the fraction of the captured carbon that will be permanently removed from the atmosphere will certainly be much lower than in natural ecosystems.

The forest and soil conservation services will be merged on 1 January 2024, providing an opportunity to change the direction of forestry towards an ecosystems approach.